A Special Interview with the Inaugural Modernism Week + Fallingwater Preservation Intern

This year marked a milestone with the launch of the Modernism Week + Fallingwater Preservation Internship. Preservation Interns work directly with Fallingwater’s preservation, collections and maintenance departments as well as visiting consultants and vendors on various projects that seek to deepen the understanding of Fallingwater’s operation as a modern house museum and site on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Supported by Modernism Week, this internship is open to international students participating in the ICOMOS-USA International Exchange Program.

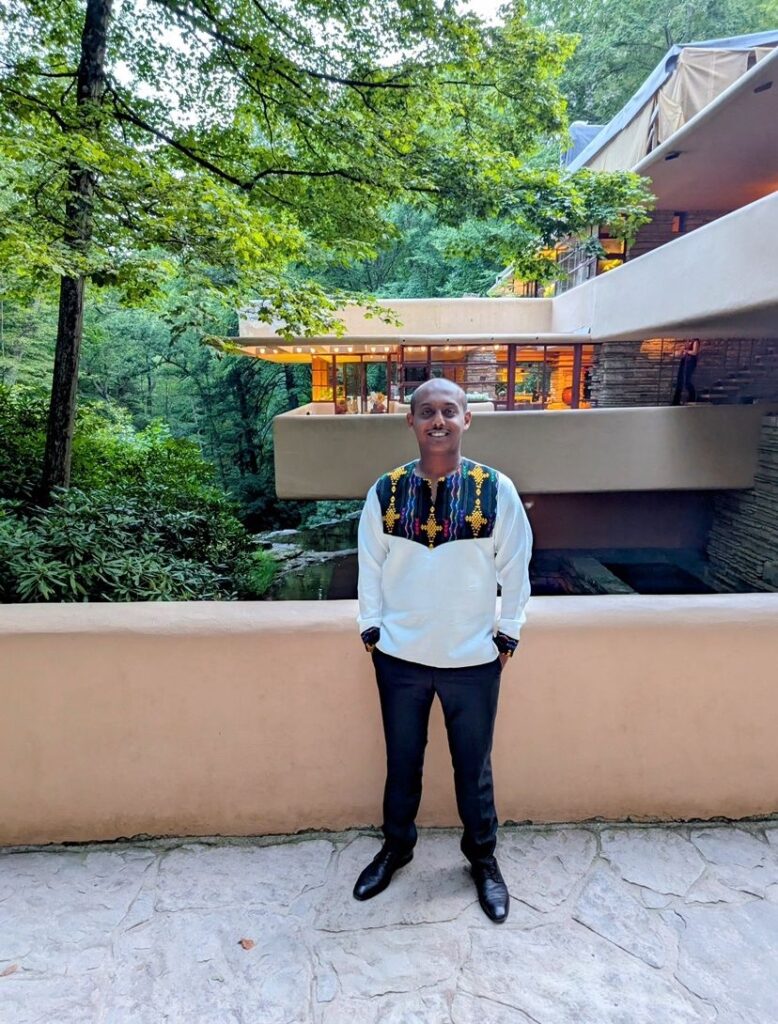

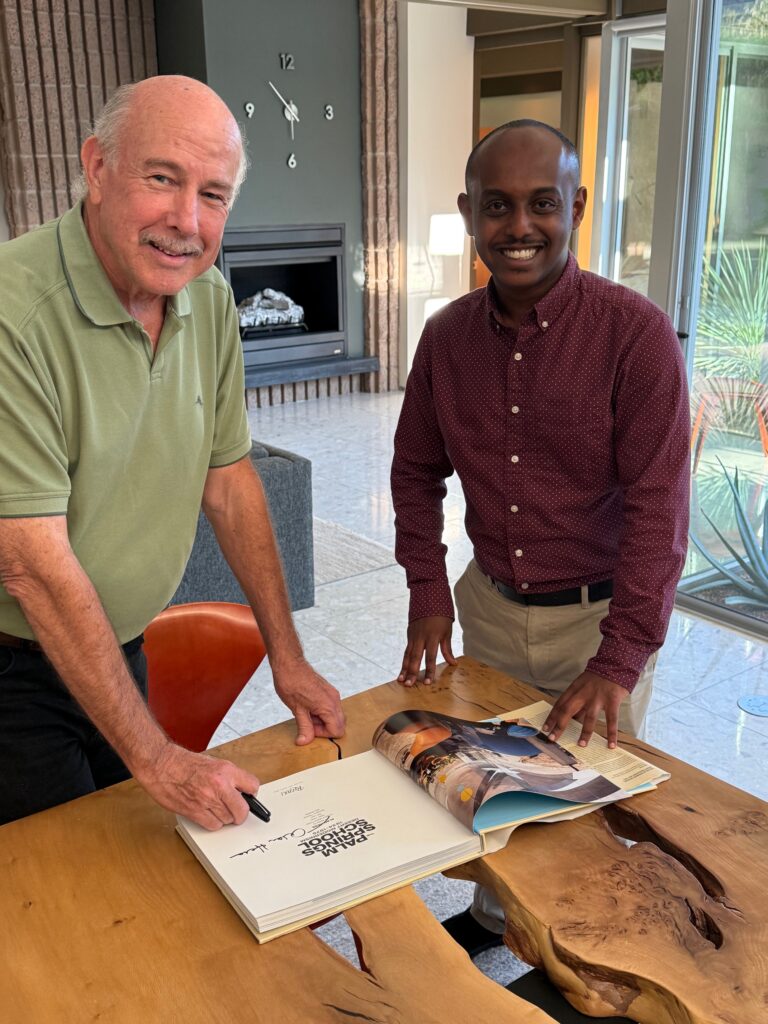

The program’s inaugural intern is Bisrat Engida, an Ethiopian architect with master’s degrees in World Heritage Studies (Germany) and Cultural Heritage (Australia). With experience spanning UNESCO, European Heritage Volunteers, and projects across Africa, Europe, and Australia, Bisrat brought a global perspective to his ten-week residency at Fallingwater, Frank Lloyd Wright’s UNESCO-listed masterpiece in Pennsylvania.

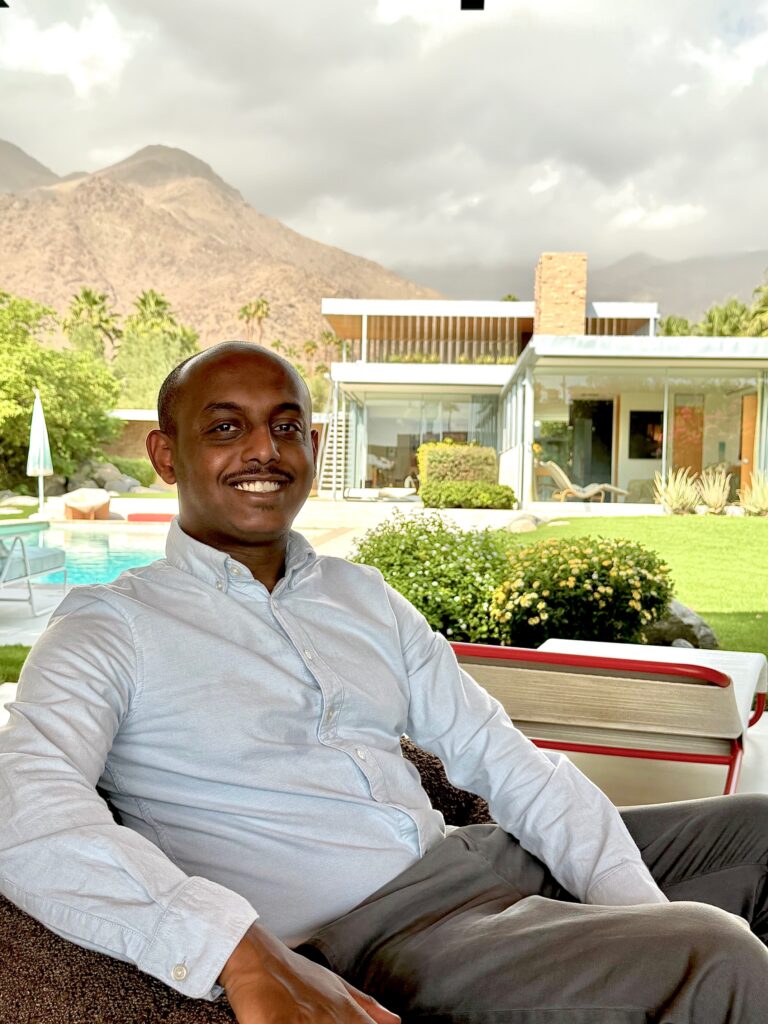

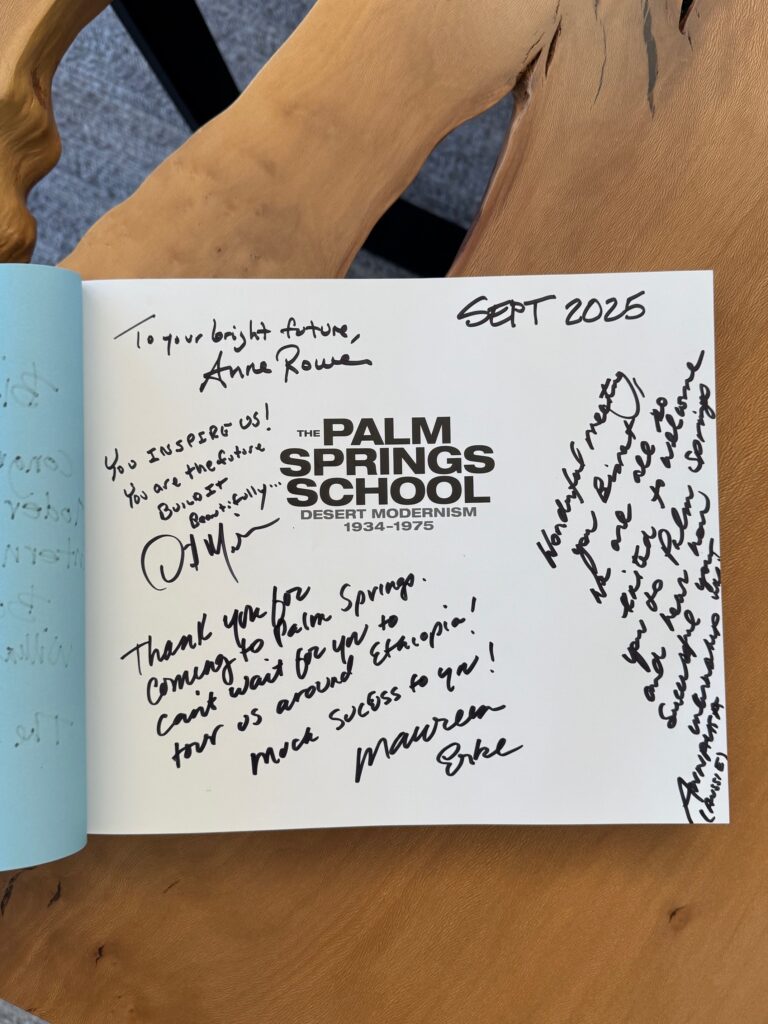

Following his work at Fallingwater this summer, he traveled to Palm Springs to experience iconic modernist sites such as the Kaufmann Desert House, Frey II, and the Grace Miller House. We spoke with him about his journey, what he learned, and how this experience will shape his future work.

How are you finding Palm Springs so far?

I love it. My first impression was that it’s very hot—I’ve never seen heat like this! But it’s amazing. It’s beautiful, the people are wonderful, and the architecture is breathtaking.

Can you share a little about your background and how you came to focus on heritage preservation?

I’m from Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. I studied architecture there and worked for about a year, but I already had doubts about traditional architecture practice. I was always drawn to old buildings—architecture that already had stories and connections. That’s what led me to study heritage preservation. I did a master’s in World Heritage Studies in Germany, and then a dual degree in Cultural Heritage in Australia. Coming from an architecture background, I’ve always been most interested in built heritage.

You’ve studied and worked in several countries. What have you observed about how different places approach heritage?

Each country deals with cultural heritage a little differently. In Europe, many countries do similar things. In Australia, I felt it was taken even more seriously. The U.S. was completely new for me. Here, there’s no centralized national authority for heritage—it differs state by state. That was surprising.

Another surprise was that the “World Heritage” brand isn’t very well known in the U.S. In most countries, becoming a World Heritage Site is a really big deal. Here, not as much. Some people even think the UN takes ownership of the site, which isn’t true. I found that fascinating because in the rest of the world, it’s a badge of pride.

What was your first impression of Fallingwater?

It’s breathtaking. When you walk up the winding road through the forest and suddenly see the house, it’s just “wow.” And that feeling stayed with me. Even after three months, every time I saw it, I was still amazed.

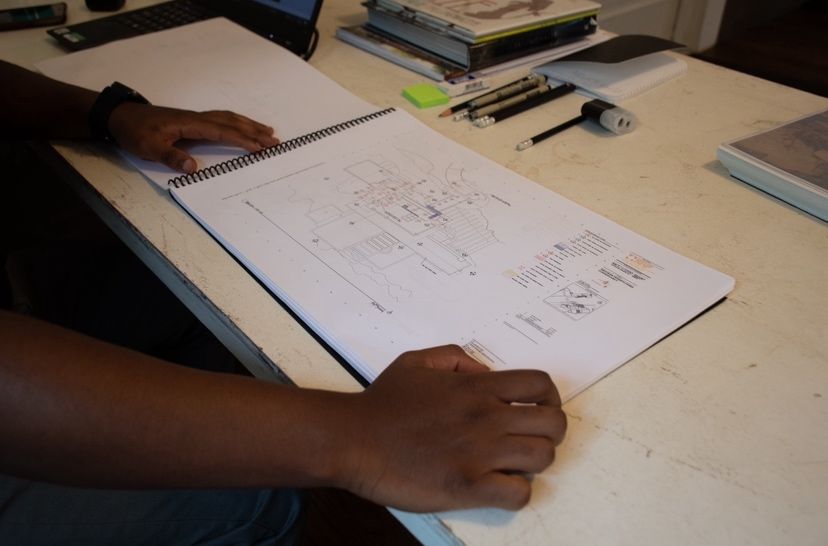

What kind of work did you do during your internship?

My main project was documenting all preservation work at Fallingwater from 1985 to 2005. I went through thousands of archival photos—many not even dated—and tried to figure out what projects happened, when, and how. Sometimes I had to ask longtime staff for help: “Do you remember when this work was done?” or “Do you know this person in the photo?” It was like detective work.

Then I created a 2025 benchmark documentation—photographing every single room, even the ones visitors never see. Now, future preservationists will have a clear reference point for what the house looked like in 2025.

All of this was organized in project management software, with details about materials, contractors, and previous repairs. If someone in 10 years notices a crack, they can look up when the last repair was, who did it, and what materials were used. It makes the history of preservation transparent and easy to access.

You also spent time interviewing staff in different departments. What did you learn from these conversations?

I realized preservation is just one part of running a World Heritage Site. You also need security, housekeeping, visitor services, catering, marketing, finance—all of it. I interviewed 12 department heads to understand their challenges.

Two questions I asked everyone were: What would you do if you had unlimited resources? and How would you manage with very limited resources? The answers were fascinating. With limited resources, almost everyone said they would focus only on the house itself and let go of everything else. With unlimited resources, people dreamed about more storage, office space, or staff—but some departments said money wasn’t really the constraint.

One thing that stood out: if preservation stopped for a year, problems might take time to show. But if security or housekeeping stopped for even one day, the site could be at risk immediately. That gave me a whole new appreciation for how everything works together.

What are some of the challenges of preserving Fallingwater?

Nobody has lived in the house since the 1960s, but Mr. Kaufmann jr. wanted it to look like the owners had “just walked out.” That means fresh flowers, fires in the fireplace, books on the shelves, art on the walls. Nothing is behind glass. It’s a very authentic atmosphere, but it creates challenges because 140,000 people visit each year.

The good thing is that people who come to Fallingwater are very intentional and respectful—they’ve made the effort to go out into the middle of the forest just to see it. That helps.

Were there any surprises during your time at Fallingwater?

I was surprised by how much I learned—honestly, those three months taught me more than five years of architecture school. And I was surprised by how long the house has required constant care. It was built in 1937, and by 1939 major maintenance had already started. There’s never been a five-year gap where nothing was done. For all its beauty, Fallingwater is also very challenging, especially with its flat roofs and humid climate.

After Fallingwater, you visited Palm Springs. What stood out to you here?

There are so many beautiful houses, it’s hard to choose. I visited the Frey House II, the Grace Miller House, the Palm Springs Visitor Center, and of course, the Kaufmann Desert House. They’re all inspiring in different ways.

The Kaufmann House was especially meaningful to me because I had just spent three months at Fallingwater, another Kaufmann family home. Seeing both houses in one summer was extraordinary. You can see similarities in the design—the disappearing corner windows, the cork tiles, and above all, the way both houses feel like they belong to their environments. Fallingwater grows out of the forest, while the Desert House feels like part of the desert itself.

I also wanted to visit the Agua Caliente Cultural Museum while I was here. It’s important to me to understand the deeper history of the place, who lived here long before these modernist houses were built. Modernism is inspiring, but so is the cultural heritage that came before it.

How will this experience impact your work, moving forward?

In Ethiopia, we have so many ancient buildings that modernist structures are often ignored. A 500-year-old site isn’t considered very old, so a 60-year-old modernist building doesn’t seem valuable to many people. I’d like to change that perception.

I’m going to talk about this experience extensively when I go back. I think it will inspire young architects in Ethiopia to start noticing and valuing modernist architecture. Personally, my eyes are now open to modernist preservation, and I’d like to keep contributing in some way.

Any final thoughts you’d like to share?

I want to thank Modernism Week, as well as Beth Edwards Harris for her generous hospitality. What are the chances of an architect from a poor country like Ethiopia getting this opportunity? It wouldn’t have happened without their support. I’m very grateful.

As the first Modernism Week + Fallingwater Preservation Intern, Bisrat Engida has set a high bar for those who will follow. His documentation work at Fallingwater and reflections in Palm Springs highlight the importance of international exchange in heritage conservation. From Ethiopia to Pennsylvania to California, his journey shows how preservation is both deeply local and profoundly global. For more information about the Modernism Week + Fallingwater Preservation Internship, click here.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Images courtesy of Bisrat Engida and Mark Davis.