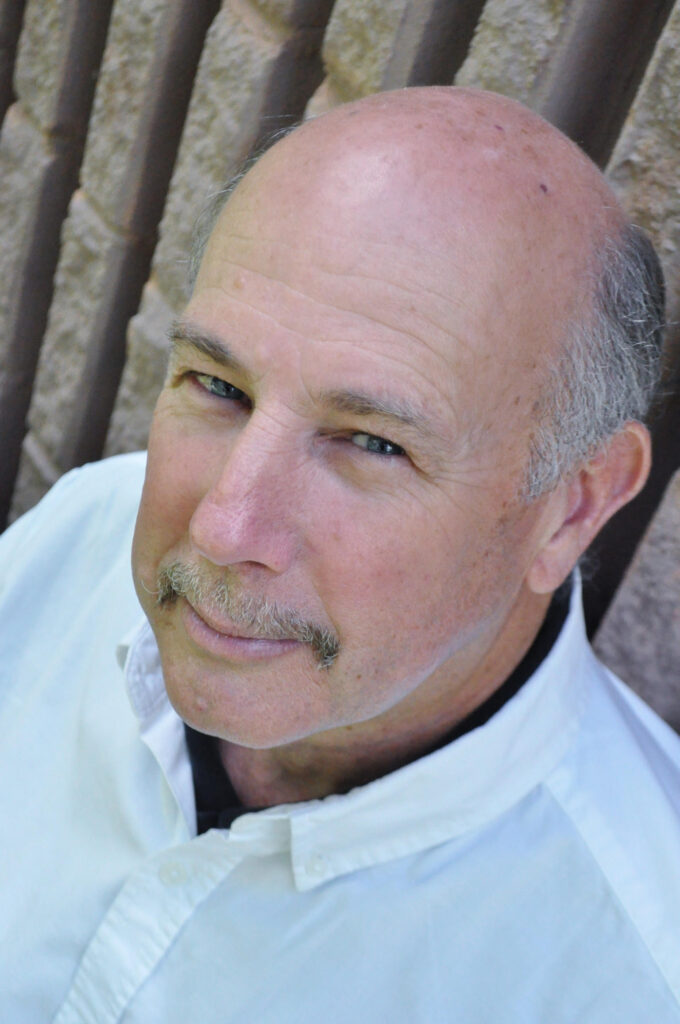

The MADE by series profiles leading voices in architecture and design. Today’s guest is architect, historian, author, and speaker Alan Hess. He has written the book (quite literally) on modernism. Read on to learn about his inspirations, the importance of architectural preservation, the future of architecture, and more.

What inspired you to become an architect, with a specific focus on modern architecture and urbanism in the mid-twentieth century?

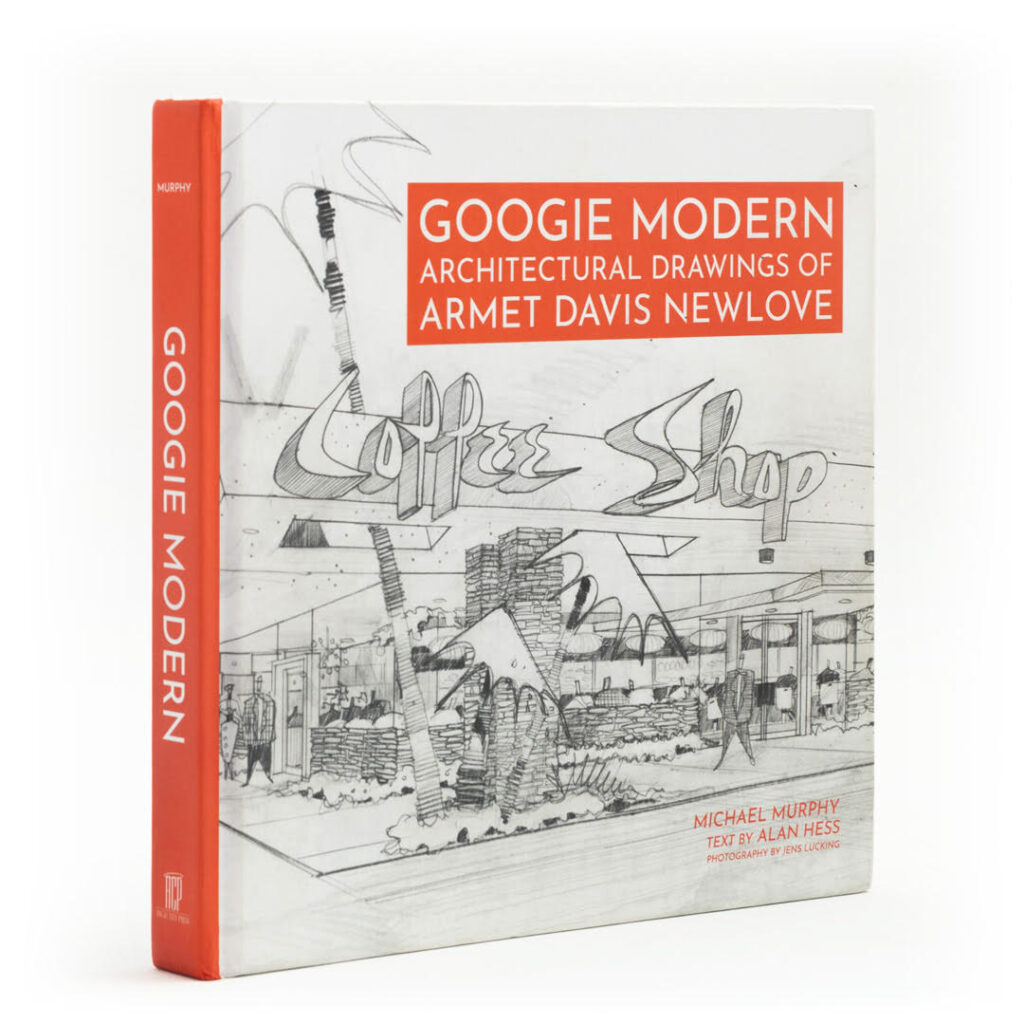

AH: I was going to be a lawyer, but when I bombed my LSATs I realized I had been handed a second chance for my future. My grandmother always had magazines on Frank Lloyd Wright around, and a philosophy course in college had introduced me to Wright and Louis Sullivan’s ideas. So I went to UCLA Architecture school. Now believe it or not, almost no one cared about modern architecture then. The Case Study houses were no big deal. But I came across a couple of small books on unknown architecture — Dan Vieyra on gas stations, Steve Izenour on White Tower diners — and when I stumbled upon the neglected and ridiculed subject of Googie Modern coffee shops, I realized I’d found the subject of my first book.

From Albert Frey and Frank Lloyd Wright, to William Pereira and Richard Neutra, you’ve researched and documented the work of some of the midcentury’s greatest architects. Of the architects you’ve met in the course of your career, were there any who surprised or particularly made an impression on you? How so?

AH: The most rewarding part of my work has been getting to know the architects who designed those great midcentury buildings. John Lautner probably surprised me the most. I had heard him talk in public, and he was always growling and complaining about bankers, businessmen, and bureaucrats stifling real architecture. So when I first interviewed him for a Fine Homebuilding magazine article on his Mauer house, I was more than a little concerned that he might kick me out of his office – I had just written an article praising Googie architecture, a term which he credited with derailing his career. But as we talked, he realized that as an architect I wanted to know how he was thinking when he designed and built. We got along fine. He even sent me a Christmas card.

What are some of your favorite underrated historical buildings?

AH: Palm Springs’ Oasis Hotel by Lloyd Wright is one of the most significant modern buildings in the entire country. It’s never been fully appreciated. Using a new concrete method, expressing its structure in its form, designing for the desert and the Sunbelt’s emerging recreational economy, Lloyd anticipated everything that would become midcentury modern.

The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts by Frank Furness has still not taken its rightful place as the birthplace of modern architecture. At first glance it looks Victorian. At second and third glance you realize that it was inspired by the modern factories that stood only a few blocks away, when post-Civil War Philadelphia was the Silicon Valley of America. Like the Oasis, it predicted everything that came later.

Today Charles Moore’s Lee Burns house in Pacific Palisades is just sitting there waiting for more architects to discover what Moore was all about: the pleasures of California living, and the rich historical heritage of Spanish architecture are essential to inspiring modern architecture.

Also, any Giant Orange roadside stand is by definition a great historical building.

How would you define architectural preservation, and why is it so important?

AH: Preservation is fundamental for good city planning. Historic buildings bring diversity. They provide the appearance, craftsmanship, and materials that today’s building industry simply cannot design or afford. And when each generation of architects in a city knows and builds on the innovations of their predecessors, they create a rich, unified urban landscape over the decades. In San Francisco Bernard Maybeck inspired William Wurster; Wurster inspired Joseph Esherick; Esherick inspired…well, you need to keep those legacies alive. We haven’t done that well in recent decades.

Where do you think the future of architecture is headed?

AH: Architecture in America is still heading down a split track. On one side there is the daring techno-whimsy of the avant-garde world of starchitects, but it’s a bit cloistered and elitist. On the other side there is the increasingly boring commercial and public architecture that thinks creative design is just an expensive frill. That’s where most of us live. What I’d like to see is the strategy taken by Googie architects so successfully: the buildings of the everyday commercial world can be practical and efficient but also lively, beauteous, and inspiring. We haven’t learned that lesson yet.

Are you working on any new books or projects at the moment?

AH: There is still so much to write about modern architecture that has been forgotten or neglected. My newest book (Googie Modern: Architectural Drawings of Armet Davis Newlove) returns to the subject I started with, but there’s still much more to discover. I’m also helping restore a 1958 Armet & Davis coffee shop on Van Nuys Blvd. (originally named Stanley Burke’s.) It will show that historic Modern buildings have a valuable role to play in today’s world.