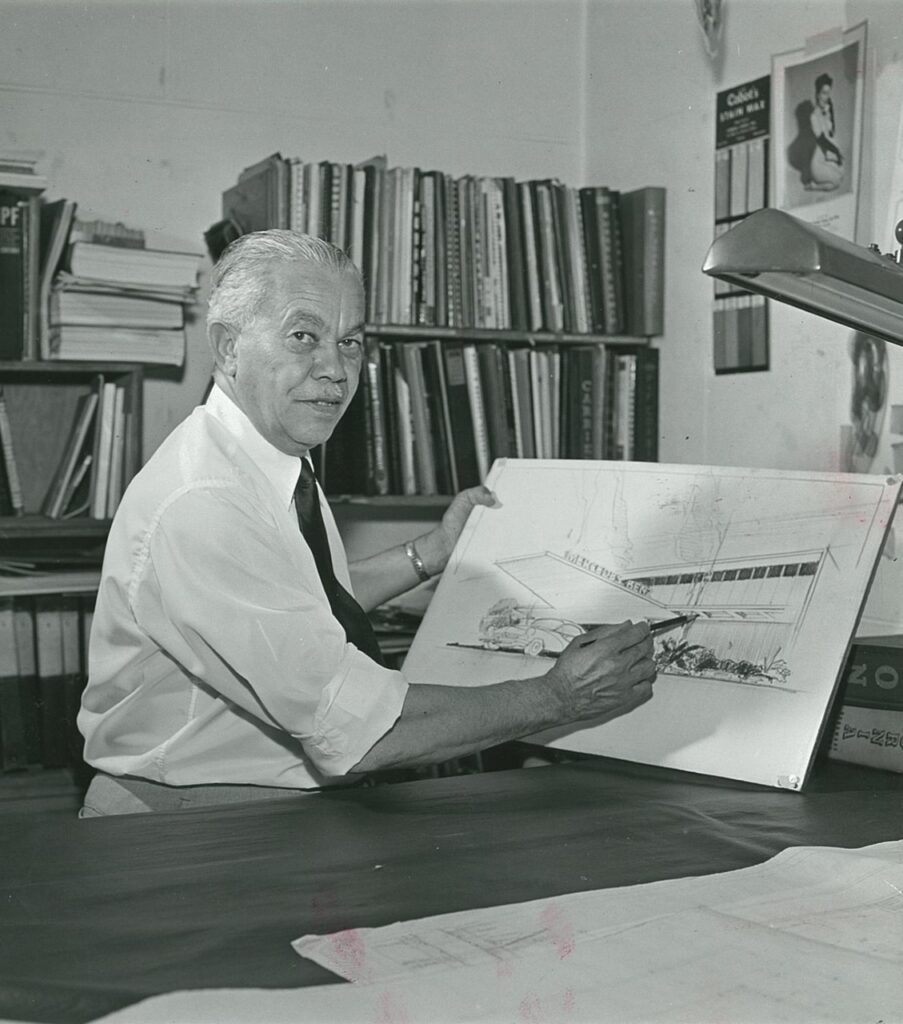

Architect Paul R. Williams’ grace, apparent in his prodigious output, enabled him to navigate a segregated Los Angeles.

It’s impossible to discuss the history of Los Angeles without mentioning architect Paul Revere Williams. In a trailblazing career that spanned nearly six decades, he’s rumored to have designed over 2,000 structures across the city, in styles ranging from Spanish Colonial to French Chateau to Tudor Revival. He also paved the way for black architects, struggling to gain a foothold in a deeply discriminatory system. His experiences embody the undercurrent of racial tensions that have long simmered beneath the city’s sunny skies.

The first African-American admitted to the American Institute of Architects (AIA), Williams, born in 1894, came of age with the city, shaping the aspirational vision of life it exported around the world. He was part of the team that advised on the 1948 movie “Mr. Blanding’s Builds His Dream House.” He designed homes for the legends of Hollywood’s Golden Age — Frank Sinatra, Barbara Stanwyck, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz — defining an idea of Hollywood glamor that continues to have resonance today. Witness The Beverly Hills Hotel: its defining characteristics, from its Crescent Wing, Polo Lounge, Fountain Coffee Shop and lobby to its distinctive font and pink and green color scheme — all Williams’ contributions — are unwavering in their elegance.

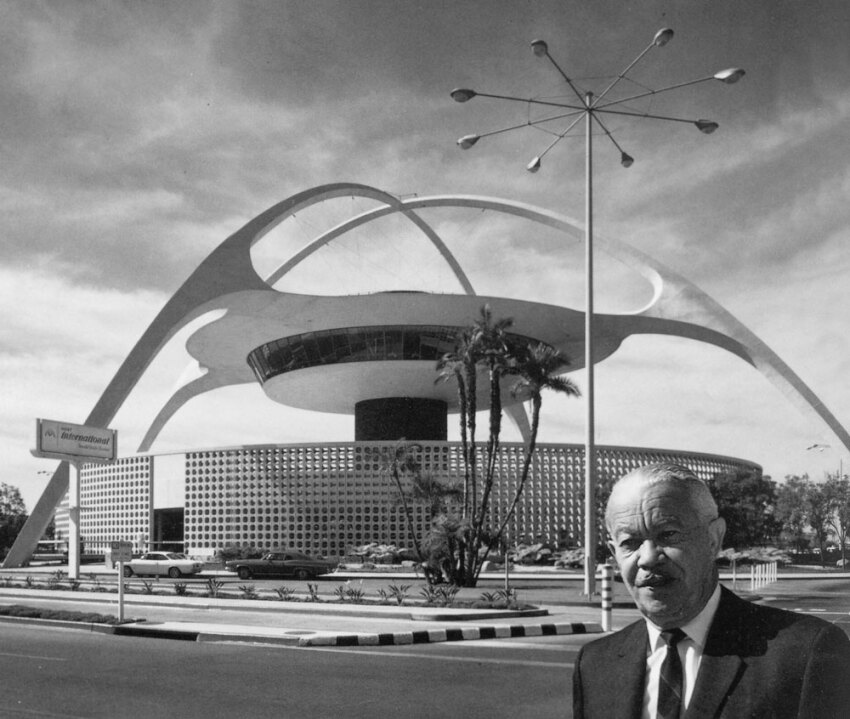

Williams also left his mark on the Southland’s commercial corridors. The Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Building, The Los Angles County Courthouse and LAX’s Theme Building (which he designed in concert with William Pereria and Charles Luckman, among others) are among the arresting public structures that bear his imprint. He worked on affordable homes and public housing. He published two inexpensive books of construction plans, New Homes of Today and Small Homes of Tomorrow, that enabled the average citizen to build a Paul R. Williams-designed home. He was especially interested in projects that promoted the African-American community. The housing unit, dormitory and restaurant at Fort Huachuca, Arizona that housed the segregated Tenth Cavalry a.k.a. the “Buffalo Soldiers”; the South Los Angeles’ Second Baptist Church; the 28th YMCA; Berkeley Square in Las Vegas; and, a handful of buildings at Washington D.C.’s Howard University are also his.

Yet, despite his accolades and prolific output, the “Architect to the Stars” was often barred from living in the very neighborhoods where he was commissioned to design homes, due to racial covenants of the time. His own home, a modest 1905 craftsman-style bungalow, was in Los Angeles’ West Adams neighborhood, one of the city’s redlined neighborhoods is now owned and being restored by architect John Arnold of KFA Architecture and his partner Curt Bouton.

The skillset that propelled him to success was forged during a turbulent childhood: his parents died from tuberculosis when he was still a toddler; a sibling was placed with a different family; and, he was the only black child at his all white school. Fortunately, his adoptive mother recognized his artistic talents and encouraged his education.

In an essay entitled “I Am a Negro”, originally published in American Magazine in 1937, and reprinted in Ebony Magazine in November 1986, Williams reflected on the impact of his racial identity on his life and early career, remembering an advisor who had counseled him against pursuing a career in architecture.

“He pointed out that I would … be obliged to depend entirely on white clients for my livelihood…You have the ability — but use it some other way. Don’t butt your head futilely against the stone wall of race prejudice.” Williams ignored the advice. “I owe it to myself and my people to accept this challenge.”

Understanding he would encounter obstacles from white people startled to discover he was black, he developed workarounds designed to put clients and colleagues at ease: he taught himself how to draw upside down, allowing him to sit across from his mostly white clients; he kept his hands in his pockets or behind his back so they wouldn’t feel pressured to shake his hand, he understood that people meeting him for the first time might try to backpedal. Recalling how he handled the situation, he described how he’d invite them to sit down so he could share a few ideas: “Theatrical tactics?,” he wrote, “Of course, but I had to win a hearing, a chance to present my wares and prove my ability….The trick worked. Frequently, it gave me needed clients.”

He had established himself as a specialist in tiny houses when, in 1929, auto tycoon E.L. Cord invited him to submit plans for a ten-acre site in Beverly Hills, warning that he was also talking to a number of other architects and wondering when Williams would be able to submit preliminary drawings. When Williams proposed that they’d be done by the following afternoon, Cord was incredulous. But, Williams fulfilled his promise and was hired for the job. That commission spurred a slew of work, including Saks Fifth Avenue in Beverly Hills.

Cord had recognized the qualities that has allowed Williams work to endure. Large or small, commercial or residential, his designs are distinguished by their impeccable sense of scale, well-proportioned rooms and gracious details. Perfectly positioned to capture a property’s best views and amplify its light, their elegant exteriors are complemented by equally graceful interiors. Tall ceilings, exquisitely rendered cabinetry, curved archways and winding staircases are hallmarks of a Williams design. Yet even his grandest buildings are inviting rather than imposing. Unfortunately, many of his notes were destroyed in the 1992 Riots when a fire destroyed the branch of the Broadway Federal Bank where they’d been stored and many of his buildings have been torn down by ignorant developers. The Paul Revere Williams project was founded to flag his work and preserve the memory and the buildings of the man who, like namesake, heralded a revolution for his native city. Yet, despite his legendary status, Williams’ structures face increasing threats of demolition or excessive alteration. In the last few decades, numerous Williams buildings have been destroyed, vanishing from the Los Angeles landscape.

MADE in Beverly Hills offers six programs that include Williams’ work, an indication of the historic, cultural and architectural significance and impact of his work:

- The Beverly Hills Hotel Signature Design Tour: Paul R. Williams (5/4, 10 am -12 pm, $130, SOLD OUT)

- Trousdale Coach Tour (5/5 – 5/7, 12 – 4 pm, $50)

- Historic Rodeo Drive Guided Walking Tour (5/6, 10 am and 12:30 pm, $30)

- Los Angeles Conservancy’s Presentation and Walking Tour of Paul R. Williams in Beverly Hills (5/7, 10 am – 12 pm, $40)

- FILM: Regarding Paul R. Williams with Photographer Janna Ireland (5/5, 2 pm, $10)

- PRESENTATION: Modern Design and Luxury in the 90210 (5/6, 2 pm, $15)